The Dance of the Two Cultures

Today the New York Times marked the death of Seamus Heaney with an above-the-fold front page photo, and a long article illustrated with quotes from his work. As I read his beautifully crafted and emotionally powerful lines I mourned our loss, while also feeling some pride that the world was giving such recognition to someone who is my compatriot.

Including Heaney, there are four Irish Nobel Laureates in Literature, which is not a bad record for a country with the population of Louisiana. In science we have not done so well though. The Nobel committee awarded only one Nobel science prize to an Irish citizen, to Ernest Walton for splitting the atom in the 1930s. When I was growing up in Ireland I never heard about Walton, but like many Irish people I knew our literature laureates well: Yeats, Shaw, Becket, and Heaney.

The Irish education system does a great job of exposing children to literature. We learn about the deep tradition of poetry in the Irish language, with its special rhyming patterns, its storytelling, and its unique imagery. Our English literature classes teach us the great Irish writers alongside the best from the rest of the English-speaking world. Even in history the recounting of our cycles of repression, rebellion, and defeat are interspersed with uplifting stories of our bards, our poets, and our writers, and the hedge-school masters who defied the Sasanaigh to teach Latin and Greek in secret.

Perhaps the association of the humanities with Irishness was most strongly forged in the early part of the twentieth century. Around that time literature flowered in the Irish Renaissance. Meanwhile political nationalism spread and strengthened, and waged an ultimately successful rebellion that resulted in an independent Ireland. Strength in literature and strength in politics seemed to go together.

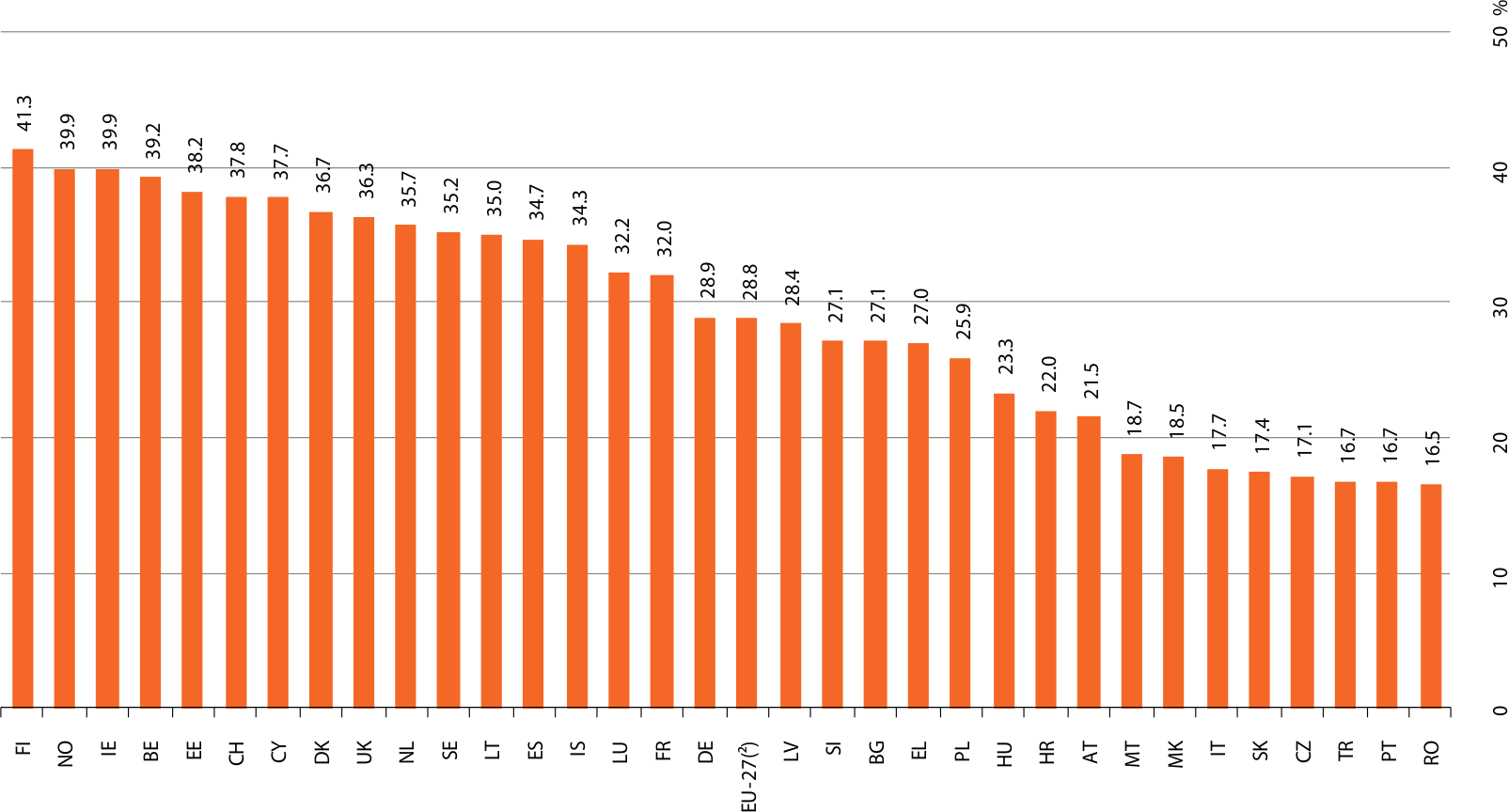

Now almost a century has passed. Look at the graph above that shows a measure of how high tech the workforce of each country in Europe is, and note that the third bar from the left is Ireland. In a generation the country has gone straight from a sleepy economy dominated by agriculture to a post-industrial economy dominated by science and technology. Of course, there has been a setback recently where some shortsighted use of financial technology combined with poor economic policy lead to an Irish banking bubble that burst disastrously when the worldwide crisis spewed its contagion across the globe. Still, I think Ireland will come back strongly in the long term, because graphs like this show that its workforce is well matched to the needs of the twenty-first century.

So despite being steeped in a national mythos so tied to writing and storytelling, the reality of Ireland is closer to that of Silicon Valley. Perhaps with this new reality, more Irish people will come to know about Walton, as well as all the Irish scientists, such as Bell, Boyle, Boole, Stokes, Beaufort, Fitzgerald, Hamilton, and Lord Kelvin, whose names live on in science. And hopefully we will add to that list, and maybe even a few more Irish scientists will make that trip to Stockholm.

So, the nation of Ireland as a whole has navigated the two cultures, of the humanities and the sciences. In my own small way I was part of that, for I distinctly remember in my mid teens confronting the decision of what academic direction I should take. I loved writing and remember the pleasure I got from turning ideas into sentences that sounded good. But I also loved Science and remember doing calculus just for fun to work out physics problems.

In the end the larger national level priorities were the decisive factor in how I chose. The government was investing in technology education, and the papers were full of the benefits of getting an engineering degree. Coming out of a working class background on the Northside of Dublin, I did not feel I had the luxury of making anything but the most pragmatic choice, so I choose electronic engineering. It had neither the romance of writing nor the excitement of scientific research, but I would likely get a job when I graduated.

And I do not regret the choice. It has given me a secure and comfortable career, a large part of it working in research labs just like I fantasized as a teenager. And I discovered pretty quickly that I really love programming, that I am one of those lucky people for whom work is never a chore, but something I look forward to every day.

Still, I sometimes wonder about the path not taken. Perhaps I could have been crafting beautiful prose not crafting elegant code, plotting stories not writing specs, observing people who could become characters in my novels not observing them to find usability bugs in my software.

And living here in San Francisco, I see the dance of the two cultures playing out here too. This city, sitting up at the end of a peninsula, has a long tradition steeped in the arts and humanities, while down at the base of the peninsula is Silicon Valley, the ultimate in technology. However in the last decade the valley has extended a pseudopod of yang into the yin of the city, and fertilized a booming high tech industry on the combined talents of designers and coders, of people who understand people and people who understand algorithms.

And this weekend half the city seems to be away in Nevada celebrating that amazing synthesis of art and technology that is Burning Man.

It feels good that the two cultures are coming together in the two places I love, the place where I live and the place where I am from.